Chondromalacia Patella / Patellofemoral syndrome

Chondromalacia Patella / Patellofemoral syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome vs. chondromalacia patellae

Chondromalacia patellae is a term sometimes treated synonymously with PFPS.[3] However, there is general consensus that PFPS applies only to individuals without cartilage damage,[3] thereby distinguishing it from chondromalacia patellae, a condition characterized by softening of the patellar articular cartilage.[1] Despite this academic distinction, the diagnosis of PFPS is typically made clinically, based only on the history and physical examination rather than on the results of any medical imaging. Therefore, it is unknown whether most persons with a diagnosis of PFPS have cartilage damage or not, making the difference between PFPS and chondromalacia theoretical rather than practical.[3] It is thought that only some individuals with anterior knee pain will have true chondromalacia patellae.[1]

Symptoms

The most common symptom of patellofemoral pain syndrome is a dull, aching pain in the front of the knee. This pain—which usually begins gradually and is frequently activity-related—may be present in one or both knees. Other common symptoms include:

- Pain during exercise and activities that repeatedly bend the knee, such as climbing stairs, running, jumping, or squatting.

- Pain after sitting for a long period of time with your knees bent, such as one does in a movie theater or when riding on an airplane.

- Pain related to a change in activity level or intensity, playing surface, or equipment.

- Popping or crackling sounds in your knee when climbing stairs or when standing up after prolonged sitting.

- The symptoms of chondromalacia patella are usually pain in the front of the knee that is aggravated by going up and down stairs, sitting for long periods of time with the knees bent (such as in a movie) and when doing deep knee bends.

Mechanism

In this syndrome, the pain is usually the result of the kneecap not tracking smoothly in the groove of the femur (the underlying thighbone) when the leg is being bent and straightened. Kneecap pain can be caused by any imbalance or dysfunction of the stabilising forces that keep the kneecap tracking smoothly in this groove, or by damage to the back surface of the kneecap.

Causes

A combination of factors may result in the kneecap not tracking smoothly, including:

- Overly tight thigh (hamstring or quadriceps) muscles;

- Tightness of the iliotibial band (the strong band of thick tissue running down the outside of the thigh), which pulls the kneecap outwards;

- Weakness of the inner thigh muscles (adductors);

- Weakness of one of the buttock muscles which stabilise the pelvis, called the gluteus medius;

- Weakness or delayed contraction of one of the large quadriceps muscles, such as the vastus medialis obliquus;

- Faulty biomechanics, such as excessive pronation (rolling in of the foot during the walking cycle;

- Swelling of the joint, due to an injury or wear and tear in the joint, will also cause reduced function in the quadriceps muscles, and this can result in anterior knee pain; and

- Osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint may cause anterior knee pain.

Often the pain develops as an overuse injury seen in long-distance runners or cyclists, or it may be initiated by a twisting injury to the knee, or even as a result of lunging or squatting.

When the knee moves, the kneecap (patella) slides to remain in contact with the lower end of the thigh bone (trochlear groove of the femur). Normally, this motion has almost no friction: the friction between these two joint surfaces is approximately 20% the friction of ice sliding against ice. If the patella and /or femur joint surface (articular cartilage) becomes softened or irregular, the friction increases. Grinding or crepitus that can be heard or felt when the knee moves is the result. This condition in which there is patellofemoral crepitus is called chondromalacia patella or patellofemoral syndrome.

The force, or pressure, with which the patella pushes against the femur is 1.8 times body weight with each step when walking on a level surface. When climbing up stairs, the force is 3.5 times body weight and when going down stairs it is 5 times body weight. When running or landing from a jump the patellofemoral force can exceed 10 or 12 times body weight.

Pressure between the patella and femur is minimized when the knee is straight or only slightly bent. Exercises and activities that require deep knee bending, jumping and landing , pushing or pulling heavy loads and stopping and starting will place very high stresses on the patellofemoral joint and the patellar tendon.

Imaging Studies

See the list below:

-

Imaging studies usually are not necessary in order for a physician to diagnose or recommend treatment for patellofemoral syndrome (PFS). Imaging studies should be considered for unusual presentations and for persons in whom the syndrome is refractory to conservative management.

- Skyline views should be included with anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographic imaging of the knee. Limited positions of flexion are available for such viewing. These radiographs provide more of an indirect observation of what is happening within the articulation.

- Lateral patellar tilt and a high-riding patella (patella alta) may be observed.

- Osteophytes or joint space narrowing may be identified, suggesting arthritic changes in the articular cartilage. [6]

-

Nuclear scans are less likely to be of value in defining PFS and are more useful in helping to identify other, less common conditions that may mimic PFS, as outlined in the differential diagnoses. When changes have occurred in the retropatellar cartilage, mild increases in uptake of radionucleotide may be observed. Increased uptake of radionucleotide is not limited to the patella; it may be seen in the proximal tibia, distal femur, or patella. [7]

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- CT scanning and MRI allow for imaging at various angles of flexion.

- CT scanning with the knee in full extension has been demonstrated to more accurately detect patellar subluxation.

- Cross-sectional viewing allows more direct visualization of the articulation between the patella and femur.

- Schutzer et al identified 3 patterns of malalignment using CT scanning [8] :

- Type 1 includes patellar subluxation without tilt.

- Type 2 is described as patellar subluxation with tilt.

- Type 3 is patellar tilt without subluxation.

Treatment

How is it treated?

Patellofemoral pain syndrome can be relieved by avoiding activities that make symptoms worse.

- Avoid sitting, squatting, or kneeling in the bent-knee position for long periods of time.

- Adjust a bicycle or exercise bike so that the resistance is not too great and the seat is at an appropriate height. The rider should be able to spin the pedals of an exercise bike without shifting weight from side to side. And the rider’s legs should not be fully extended at the lowest part of the pedal stroke.

- Avoid bent-knee exercises, such as squats or deep knee bends.

Other methods to relieve pain include:

- Taking nonprescription anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen, to decrease swelling, stiffness, and pain. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

- Ice and rest. You can also try heat to see if it helps.

- Physical therapy exercises. Exercises may include stretching to increase flexibility and decrease tightness around the knee, and straight-leg raises and other exercises to strengthen the quadriceps muscle.

- Taping or using a brace to stabilize the kneecap.

- Surgery.

Short-term

- Initial treatment may involve taping of the kneecap to hold it in a more ideal position to relieve pain. A sports doctor or physiotherapist will be able to show you how to tape the knee correctly to pull it back into alignment.

- Simple pain relief medicine such as paracetamol and sometimes a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may also help.

- When the symptoms first develop they are best treated by icing the knee for 10-20 minutes after activity.

- It is also advisable to avoid any activities that exacerbate the pain.

Long-term

- Rehabilitation involving stretching and strengthening exercises for specific muscles to achieve correct balance of the stabilising muscles around the kneecap.

- Strengthening of stabilising buttock muscles, that when activating properly, enable the muscles about the knee to function more effectively.

- Orthotics are useful for those with biomechanical abnormalities, particularly excessive pronation of the foot (rolling in).

- Your doctor or physiotherapist may design an individual exercise programme for you. Such a programme will include a graded increase in activity. It is important to do these exercises on a daily basis to maximise the chance of recovery, which will generally take about 6 weeks.

- If there is significant swelling of the knee, further assessment and investigation will be needed.

The best treatment for patellofemoral syndrome is to avoid activities that compress the patella against the femur with force. This means avoiding going up and down stairs and hills, deep knee bends, kneeling, step-aerobics and high impact aerobics. Do not wear high heeled shoes. Do not do exercises sitting on the edge of a table lifting leg weights (knee extension). An elastic knee support that has a central opening cut out for the kneecap sometimes helps. Applying ice packs for 20 minutes after exercising helps. Aspirin, Aleve or Advil sometimes helps.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Treatment

Approximately 90% of patello-femoral syndrome sufferers will be pain-free within six weeks of starting a physiotherapist guided rehabilitation program for patellofemoral pain syndrome.

For those who fail to respond, surgery may be required to repair associated injuries such as severely damaged or arthritic joint surfaces.

The aim of treatment is to reduce your pain and inflammation in the short-term and, then more importantly, correct the cause to prevent it returning in the long-term.

Phase 1 – Injury Protection: Pain Relief & Anti-inflammatory

- As with most soft tissue injuries the initial treatment is – Rest, Ice and Protection.

- Anti-inflammatory medication is often recommended to reduce pain.

Phase 2: Restore Full Muscle Length

- It is important to regain normal muscle length to improve your lower limb biomechanics.

- A specific stretching program is prescribed in this phase of treatment to address any muscle length issues,

Phase 3: Normalise Quadriceps Muscle Balance

- In order to prevent a recurrence, the quadriceps muscle balance and its effect on the patellar tracking will be addressed in this stage via a specific knee strengthening program

Phase 4 : Normalise Foot & Hip Biomechanics

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome can occur from poor foot biomechanics (eg flat foot) or poor hip control.

- To prevent a recurrence, your foot and hip control will be addressed.

- In some instances, you may require a foot orthotics and footwear changes to control abnormal foot and leg biomechanics along with a hip stabilisation program.

Epidemiology /Etiology

PFPS can be due to a patellar trauma, but it is more often a combination of several factors (multifactorial causes): overuse and overload of the patellofemoral joint, anatomical or biomechanical abnormalities, muscular weakness, imbalance or dysfunction. It’s more likely that PFPS is worsened and resistive to treatment because of several of these factors.

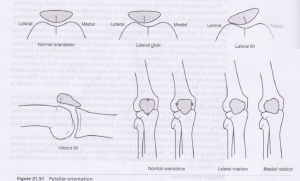

One of the main causes of PFPS is the patellar orientation and alignment. (fig.1) When the patella has a different orientation, it may glide more to one side of the facies patellaris (femur) and thus can cause overuse/overload (overpressure) on that part of the femur which can result in pain, discomfort or irritation. There are different causes that can provoke such deviations.

The patellar orientation varies from one patient to another; it can also be different from

the left to right knee in the same individual and can be a result of anatomical malalignments. A little deviation of the patella can cause muscular imbalances, biomechanical abnormalities … which can possibly result in PFPS. Conversely, muscular imbalances or biomechanical abnormality can cause a patellar deviation and also provoke PFPS. For example:

When the Vastus Medialis Obliquus isn’t strong enough, the Vastus Lateralis can exert a higher force and can cause a lateral glide, lateral tilt or lateral rotation of the patella which can cause an overuse of the lateral side of the facies patellaris and result in pain or discomfort. The opposite is possible but a medial glide, tilt or rotation is rare. Another muscle and ligament that can cause a patellar deviation is the iliotibial band or the lateral retinaculum in case there is an imbalance or weakness in one of these structures. (see table1)

PFPS can also be due to knee hyperextension, lateral tibial torsion, genu valgum or varus, increased Q-angle, tightness in the iliotibial band, hamstrings or gastrocnemius.

Sometimes the pain and discomfort is localized in the knee, but the source of the problem is somewhere else. A pes planus (pronation) or a Pes Cavus (supination) can provoke PFPS. Foot pronation (which is more common with PFPS) causes a compensatory internal rotation of the tibia or femur that upsets the patellofemoral mechanism. Foot supination provides less cushioning for the leg when it strikes the ground so more stress is placed on the patellofemoral mechanism.

The hip kinematics can also influence the knee and provoke PFPS. A study has shown that patients with PFPS displayed weaker hip abductor muscles that were associated with an increase in hip adduction during running.

Table 1

| Muscular etiologies of PFPS | |

| Etiology | Pathophysiology |

| Weakness in the quadriceps | It may adversly affect the PF mechanism.

Strengthening is often recommended. |

| Weakness in the medial quadriceps | It allows the patella to track too far laterally.

Strengthening of the VMO is often recommended. |

| Tight iliotibial band | It places excessive lateral force on the patella and can

also externally rotate the tibia, upsetting the balance of the PF mechanism. This can lead to excessive lateral tracking of the patella. |

| Tight hamstrings muscles | It places more posterior force on the knee, causing

pressure between the patella and the femur to increase. |

| Weakness of tightness in the hip muscles | Dysfunction of the hip external rotators results in

compensatory foot pronation. |

| Tight calf muscles | It can lead to compensatory foot pronation and can

increase the posterior force on the knee. |

Activity modification

As overuse of the knee is a primary contributing factor to patellofemoral syndrome, activity modification is one way to reduce further damage to the knee and prevent a recurrence of the condition.

People who experience patellofemoral syndrome may wish to reduce or avoid activities that include repetitive high-impact actions, such as:

- running

- jumping

- kneeling

- squatting

- lunging

- going up and down stairs or other steep inclines

- sitting for long periods of time

Examples of low-impact exercises that put less strain on the knees include:

- swimming

- cycling

- water aerobics

- using elliptical machines

STRENGTHENING VASDUS MEDIALIS

The Clamshell

A common and simple exercise to help keep the gluteals conditioned includes something called the ‘clamshell’. While lying on one side bend both knees to 90 degrees, and keep the feet in alignment with the hips. While keeping the pelvis still (belly button pointing slightly downward) and your feet together, raise the top knee. Completing 20 repetitions for three sets should make you feel as if someone poked you in the middle of your back pocket. Check out this brief video to make sure your technique is good: