a1

07

A@@

07

A@@

valsartan, telmisartan, and candesartan

best outcomes

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) are two such drugs commonly used to treat patients with hypertension. As generic ARBs have hit the market, many providers and patients are turning to ARBs over ACEIs owing to their similar effectiveness and improved tolerability. Evidence suggesting that ARBs have other benefits over ACEIs might really tip the scales in the favor of ARBs. Of note, researchers have postulated that ARBs might play a role in decreasing cognitive decline as a result of vascular changes in both hypertension and dementia.[1] Observational studies and prospective clinical trials have investigated this potential neuroprotective benefit and found slight improvements in cognitive function with ARBs relative to other antihypertensive drugs.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

Li and colleagues[3] evaluated the incidence of dementia and the rate of disease progression among hypertensive patients aged 65 years or older (n = 819,491) taking ARBs, lisinopril, or other cardiovascular comparators (eg, beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers). Patients were followed over a 4-year period, with results adjusted for age, diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease. In patients without a prior diagnosis of Alzheimer disease or dementia, the use of ARBs was associated with a 19% lower risk of developing Alzheimer disease or dementia versus lisinopril; compared with other antihypertensives, the risk was 16% lower for Alzheimer disease and 24% lower for dementia. In addition, ARB use was associated with a significantly lower risk for nursing home admissions and death compared with lisinopril and other antihypertensive drugs.

Goh and colleagues[4] compared the risk for dementia among patients (n = 426,089) receiving therapy with ACEIs or ARBs. Almost all patients were being treated for hypertension, and about 75% were older than 55 years and did not have diabetes. Compared with ACEIs, use of an ARB was associated with an 8% reduction in the risk for dementia in the adjusted analysis. The impact of ARB exposure on dementia diagnoses was most apparent within the first year, as their use was associated with a 40% lower risk for dementia versus ACEIs during this time frame. However, no long-term neuroprotective benefit was observed beyond 3 years of therapy.

More recently, Ho and colleagues[5] examined whether the use of ARBs was associated with improved memory preservation compared with the use of other antihypertensive drugs. A total of 1626 adults without dementia aged 55-91 years were included. Researchers assessed data from three groups: hypertensive patients treated with ARBs, hypertensive patients treated with other antihypertensives, and patients without hypertension. In general, over 3 years of follow-up, hypertensive patients in the non-ARB group had worse cognitive outcomes compared with both normotensive patients and hypertensive patients treated with ARBs, whereas hypertensive patients treated with ARBs had similar improvements in short- and long-term memory compared with normotensive patients. In addition, patients using blood-brain barrier (BBB)–crossing ARBs (ie, valsartan, telmisartan, and candesartan) were compared with those using non-BBB–crossing ARBs. Users of BBB-crossing ARBs had improved long-term memory-related outcomes and a smaller volume of white-matter hyperintensities. The researchers concluded that ARBs, particularly BBB-crossing ARBs such as valsartan, telmisartan, and candesartan, are probably associated with greater memory preservation and less white-matter volume than other antihypertensive medications.

To further explain the potential neuroprotective mechanism, recall that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) has effects on the pathophysiology of dementia through other mechanisms outside of the effects on cerebral blood flow and vascular resistance. These mechanisms include tau phosphorylation, amyloid metabolism, and oxidative stress. In addition, angiotensin II blocks the release of acetylcholine in cholinergic neurons, adding to the neurodegenerative effect seen in Alzheimer disease.[2] These additional mechanisms help explain why RAAS blockade is superior to blood pressure control alone for improving cognition-related outcomes.

In addition, two types of angiotensin II receptor exist in humans. ARBs only block activity at the damaging angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1), whereas ACEIs reduce receptor activity at both the damaging AT1 receptor and the beneficial AT2 receptor. Therefore, some have suggested that ARBs provide a neuroprotective effect for memory, whereas ACEIs may have paradoxical neurotoxicity.[10]

Also of note, a clinical trial is actively recruiting patients aged 65-80 years with a family history of dementia to evaluate the effects of aerobic exercise and pharmacologic treatment (ie, losartan, amlodipine, atorvastatin) on the risk for Alzheimer disease. Hopefully, these results will help to further clarify the benefit of ARBs in memory preservation and dementia prevention.

Multiple studies show a statistical correlation between memory preservation and the use of ARBs in patients with hypertension. And although no large-scale prospective, randomized, controlled studies have defined the magnitude of cognitive decline (or preservation) with ARBs relative to other antihypertensive drugs, it seems prudent to start patients with hypertension or diabetes and a strong family history of dementia on therapy with ARBs versus ACEIs or other antihypertensive drugs. Unfortunately, the widespread recalls of popular ARBs contaminated with the potential carcinogen N-methylnitrosobutyric acid has limited the number of ARBs available for patients initiating or switching to this class. If this issue is resolved, it seems likely that the popularity of ARBs over ACEIs will continue to grow. However, any therapy should be individualized and tempered by other compelling concurrent disease state considerations.

Chondromalacia patellae is a term sometimes treated synonymously with PFPS.[3] However, there is general consensus that PFPS applies only to individuals without cartilage damage,[3] thereby distinguishing it from chondromalacia patellae, a condition characterized by softening of the patellar articular cartilage.[1] Despite this academic distinction, the diagnosis of PFPS is typically made clinically, based only on the history and physical examination rather than on the results of any medical imaging. Therefore, it is unknown whether most persons with a diagnosis of PFPS have cartilage damage or not, making the difference between PFPS and chondromalacia theoretical rather than practical.[3] It is thought that only some individuals with anterior knee pain will have true chondromalacia patellae.[1]

The most common symptom of patellofemoral pain syndrome is a dull, aching pain in the front of the knee. This pain—which usually begins gradually and is frequently activity-related—may be present in one or both knees. Other common symptoms include:

In this syndrome, the pain is usually the result of the kneecap not tracking smoothly in the groove of the femur (the underlying thighbone) when the leg is being bent and straightened. Kneecap pain can be caused by any imbalance or dysfunction of the stabilising forces that keep the kneecap tracking smoothly in this groove, or by damage to the back surface of the kneecap.

A combination of factors may result in the kneecap not tracking smoothly, including:

Often the pain develops as an overuse injury seen in long-distance runners or cyclists, or it may be initiated by a twisting injury to the knee, or even as a result of lunging or squatting.

When the knee moves, the kneecap (patella) slides to remain in contact with the lower end of the thigh bone (trochlear groove of the femur). Normally, this motion has almost no friction: the friction between these two joint surfaces is approximately 20% the friction of ice sliding against ice. If the patella and /or femur joint surface (articular cartilage) becomes softened or irregular, the friction increases. Grinding or crepitus that can be heard or felt when the knee moves is the result. This condition in which there is patellofemoral crepitus is called chondromalacia patella or patellofemoral syndrome.

The force, or pressure, with which the patella pushes against the femur is 1.8 times body weight with each step when walking on a level surface. When climbing up stairs, the force is 3.5 times body weight and when going down stairs it is 5 times body weight. When running or landing from a jump the patellofemoral force can exceed 10 or 12 times body weight.

Pressure between the patella and femur is minimized when the knee is straight or only slightly bent. Exercises and activities that require deep knee bending, jumping and landing , pushing or pulling heavy loads and stopping and starting will place very high stresses on the patellofemoral joint and the patellar tendon.

See the list below:

Imaging studies usually are not necessary in order for a physician to diagnose or recommend treatment for patellofemoral syndrome (PFS). Imaging studies should be considered for unusual presentations and for persons in whom the syndrome is refractory to conservative management.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Patellofemoral pain syndrome can be relieved by avoiding activities that make symptoms worse.

Other methods to relieve pain include:

The best treatment for patellofemoral syndrome is to avoid activities that compress the patella against the femur with force. This means avoiding going up and down stairs and hills, deep knee bends, kneeling, step-aerobics and high impact aerobics. Do not wear high heeled shoes. Do not do exercises sitting on the edge of a table lifting leg weights (knee extension). An elastic knee support that has a central opening cut out for the kneecap sometimes helps. Applying ice packs for 20 minutes after exercising helps. Aspirin, Aleve or Advil sometimes helps.

Approximately 90% of patello-femoral syndrome sufferers will be pain-free within six weeks of starting a physiotherapist guided rehabilitation program for patellofemoral pain syndrome.

For those who fail to respond, surgery may be required to repair associated injuries such as severely damaged or arthritic joint surfaces.

The aim of treatment is to reduce your pain and inflammation in the short-term and, then more importantly, correct the cause to prevent it returning in the long-term.

Phase 1 – Injury Protection: Pain Relief & Anti-inflammatory

Phase 2: Restore Full Muscle Length

Phase 3: Normalise Quadriceps Muscle Balance

Phase 4 : Normalise Foot & Hip Biomechanics

PFPS can be due to a patellar trauma, but it is more often a combination of several factors (multifactorial causes): overuse and overload of the patellofemoral joint, anatomical or biomechanical abnormalities, muscular weakness, imbalance or dysfunction. It’s more likely that PFPS is worsened and resistive to treatment because of several of these factors.

One of the main causes of PFPS is the patellar orientation and alignment. (fig.1) When the patella has a different orientation, it may glide more to one side of the facies patellaris (femur) and thus can cause overuse/overload (overpressure) on that part of the femur which can result in pain, discomfort or irritation. There are different causes that can provoke such deviations.

PFPS can also be due to knee hyperextension, lateral tibial torsion, genu valgum or varus, increased Q-angle, tightness in the iliotibial band, hamstrings or gastrocnemius.

Sometimes the pain and discomfort is localized in the knee, but the source of the problem is somewhere else. A pes planus (pronation) or a Pes Cavus (supination) can provoke PFPS. Foot pronation (which is more common with PFPS) causes a compensatory internal rotation of the tibia or femur that upsets the patellofemoral mechanism. Foot supination provides less cushioning for the leg when it strikes the ground so more stress is placed on the patellofemoral mechanism.

The hip kinematics can also influence the knee and provoke PFPS. A study has shown that patients with PFPS displayed weaker hip abductor muscles that were associated with an increase in hip adduction during running.

Table 1

| Muscular etiologies of PFPS | |

| Etiology | Pathophysiology |

| Weakness in the quadriceps | It may adversly affect the PF mechanism.

Strengthening is often recommended. |

| Weakness in the medial quadriceps | It allows the patella to track too far laterally.

Strengthening of the VMO is often recommended. |

| Tight iliotibial band | It places excessive lateral force on the patella and can

also externally rotate the tibia, upsetting the balance of the PF mechanism. This can lead to excessive lateral tracking of the patella. |

| Tight hamstrings muscles | It places more posterior force on the knee, causing

pressure between the patella and the femur to increase. |

| Weakness of tightness in the hip muscles | Dysfunction of the hip external rotators results in

compensatory foot pronation. |

| Tight calf muscles | It can lead to compensatory foot pronation and can

increase the posterior force on the knee. |

As overuse of the knee is a primary contributing factor to patellofemoral syndrome, activity modification is one way to reduce further damage to the knee and prevent a recurrence of the condition.

People who experience patellofemoral syndrome may wish to reduce or avoid activities that include repetitive high-impact actions, such as:

Examples of low-impact exercises that put less strain on the knees include:

STRENGTHENING VASDUS MEDIALIS

A common and simple exercise to help keep the gluteals conditioned includes something called the ‘clamshell’. While lying on one side bend both knees to 90 degrees, and keep the feet in alignment with the hips. While keeping the pelvis still (belly button pointing slightly downward) and your feet together, raise the top knee. Completing 20 repetitions for three sets should make you feel as if someone poked you in the middle of your back pocket. Check out this brief video to make sure your technique is good:

Patellar tendinitis is characterized by inflammation and pain at the patellar tendon (the tendon below the kneecap). This structure is the tendon attachment of the quadriceps (thigh) muscles to the leg, which is important in straightening the knee or slowing the knee during bending or squatting. Patellar Tendonitis is typically a grade 1 or 2 strain of the tendon. A grade 1 strain is a mild strain. There is a slight pull without obvious tearing (referred to as microscopic tendon tearing). There is no loss of strength, and the tendon is the correct length. A grade 2 strain is a moderate strain, which involves tearing of tendon fibers within the substance of the tendon or at the bone-tendon junction. The length of the tendon is usually increased, and there is decreased strength. A grade 3 strain is a complete rupture of the tendon.

The patellar tendon originates from the anterior aspect of the extensor hood, inferior to the patellar apex. The distal portion of the patellar tendon inserts on the tibial tubercle. The patellar tendon is a monotonous band of fibrocartilaginous tissue.3 Though Jumper’s Knee was once referred to as patellar tendonitis, it is now well established in histopathologically and biochemically analyzed tissue samples excised from the patellar tendons of patients with acute symptoms of Jumper’s Knee that inflammatory cellular infiltrates are absent.4,7 This confirms that the mechanism of disease in Jumper’s Knee is that of a degenerative tendinopathy (tendinosis)5,6 rather than that of an inflammatory tendinitis. In the setting of patellar tendinopathy associated with jumper’s knee, the area of abnormal signal intensity on MRI corresponds to a region of tenocyte hyperplasia, angiofibroblastic tendinosis, loss of coherent collagenous architecture and microtears.4 With more advanced disease, macrotears and frank discontinuity may ensue. Rarely, an avulsion fracture at the apical patellar enthesis may be found.

Patellar tendinosis may be classified into four stages of injury. They are as follows:

Stage 1: Pain after activity, without functional impairment

Stage 2:

Stage 3:

Stage 4: Complete tendon rupture requiring surgical repair

To evaluate for the presence of injury, the following test can be conducted:

Ask the patient to lie on unaffected side on a treatment table.

Passively flex the patient’s knee.

A positive sign for jumper’s knee is present if the patient feels pain at 120 degrees passive knee flexion or anytime during resisted knee extension.

The ability of MRI to acquire multiplanar images, in concert with its high soft tissue contrast, makes MR imaging the most effective diagnostic modality in the evaluation of Jumper’s Knee. T1, proton density and/or T2-weighted sagittal and axial sequences are employed to evaluate the patellar tendon. Coronal sequences are of limited value due to volume averaging artifacts and the non-orthogonal slice orientation. On MR images, the normal patellar tendon demonstrates homogenous low signal intensity (4a). Exceptions to this rule occur proximally, where the posterior margin of the tendon may show thin, linear, intermediate signal intensity striations, and distally, where mildly increased signal intensity may be noted at the triangle proximal to the tibial tubercle enthesis. A normal patellar tendon should not exceed 7mm in AP diameter.4,9 The tendon is semilunar to half round in geometry, with a convex anterior border. A constant feature is that of a well-defined posterior border (5a).

With Jumper’s Knee, the most reliable MRI finding is focal proximal 3rd tendon thickening with an associated increase in AP diameter greater than 7mm.9 Focal T2 hyperintensity within the proximal tendon is most commonly seen involving the medial one-third of the tendon (6a),4 and may extend to involve the central third of the tendon. Mild, subtle tendonopathy may not affect the entire A-P diameter of patellar tendon (7a). More severe tendinopathy demonstrates full thickness involvement by intrasubstance signal and T2 hyperintensity (8a,8b). In addition, an indistinct posterior tendon border may also be seen. Edema may be present within the adjacent Hoffa’s fat pad, with irregular T2 hyperintensity replacing normal fat signal. Partial thickness (9a,10a) and complete tears may also occur (11a,11b).

Eccentric Quadriceps and Patellar Tendon Exercises

http://eccentric-exercises.blogspot.com.au/2007/12/my-eccentric-exercise-protocol.html

Symptoms of patellar tendonitis largely involve pain and tenderness in the area surrounding the kneecap. Any activity that places additional stress on the kneecap, like squatting or kneeling,l produce more severe pain. If untreated, these signs of patellar tendonitis will only grow worse and will begin to interfere with normal activities like climbing stairs.

Understanding how to heal patellar tendonitis begins by differentiating between the acute and chronic forms of the injury.

Acute patellar tendonitis results from a single accident or incident, causing symptoms almost immediately. Acute cases are most common in athletes.

The chronic form of the condition may be easy to overlook, as symptoms develop gradually, allowing the patient to continue regular activity, causing further damage. If untreated, chronic patellar tendonitis will develop symptoms as severe as its acute counterpart.

Treatment for patellar tendonitis can focus on treating immediate pain or addressing the underlying cause. By approaching the problem from both sides, you will both heal your patellar tendonitis and enjoy a manageable recovery process.

The best treatment for patellar tendonitis in the short term is simple rest. Short-term pain relief is important to your daily life, before finding a long-term cure for patellar tendonitis. Avoiding heavy physical activity will allow the tendons to repair themselves in a matter of days or weeks. Boost the effectiveness of this patellar tendonitis cure by incorporating hot and cold therapy and reducing swelling with patellar tendonitis taping or a compression sleeve.

Compression sleeves reduce inflammation and improve circulation to encourage healing. ( See Product)

Compression sleeves reduce inflammation and improve circulation to encourage healing. ( See Product)

Once your immediate symptoms are under control, explore long-term solutions for treating patellar tendonitis:

Exercises for patellar tendonitis in the knee are one way to strengthen muscles for a faster and healthier recovery process. In addition to speeding recovery, physical therapy for patellar tendonitis will protect against future injury.

Adjust the intensity of the patellar tendonitis stretches below to fit your own needs and limitations. Pushing yourself too hard can worsten the condition, leaving you in a worse place than when you started.

Speak to your doctor before attempting the following stretches for patellar tendonitis.

Stand about 18 inches from a wall. Take one step forward with your uninjured leg and place both palms flat on the wall. From this position, lean forward and bend your injured leg slightly until you feel a stretch in your calf.

The quads are essential to a functioning knee joint, which makes quad stretches key patellar tendonitis physical therapy exercises. Standing, bend your injured leg at the knee. Use your hand to pull the ankle upward toward your hips, stabilize yourself against a wall if necessary. Lean forward to stretch the muscle. You should feel a slight burning sensation in your upper leg.

The hamstring is one of the most commonly injured leg muscles, so hamstring stretches are a crucial part of your patellar tendonitis recovery exercise regimen. Stand and lean forward to touch your toes while keeping your knees locked. Reach down as far as you are able.

The best physical therapy exercises for patellar tendonitis include a fair share of eccentric training. Begin in a standing position, using a slant board if you have one available. Perform an eccentric decline squat by extending your uninjured leg forward and squatting slowly on your injured leg. Use a wall or chair for support if necessary. Return to standing position, and repeat 5 to 10 times.

Testing flexibility – A good place to start is testing the flexibility of the hip flexor and quadriceps muscles. This can be tested by performing the Thomas test.

Sit on the end of a couch and pull the knee up to your chest. Holding this position, lay back onto the couch. The thigh of the free leg should be horizontal. If it rides up, this indicates possible tight hip flexor muscles (Rectus femoris or Iliopsoas). The shin of the free leg should hang vertically. If not then this may indicate tight Quadriceps muscles.

Quadriceps stretch – The quads can be stretched in either the standing or laying position. In standing you can hold onto something for balance if you need to or try holding your ear with the opposite arm. Aim to keep the knees together and pull the leg up straight not twisted. You should feel a stretch at the front of the leg which should not be painful. In the early acute stages of treatment hold stretches for around 10 seconds. Later on when the inflammation has gone stretches should be held for around 30 seconds. Repeat 3 times and stretch at least 3 times a day.

Play quadriceps muscle stretch video.

Hip flexor stretch – This exercise stretches the iliopsoas muscle and rectus remoris. Place one knee on the floor and the other foot out in front with the knee bent. Be careful to use on a mat or padding under the painful knee so at not to aggravate the injury. Push your hips forwards and keep your back upright. You should feel a stretch at the front of the hip and upper thigh. Hold for 10-30 seconds. Repeat 3 times and stretch at least 3 times a day. This exercise stretches the Rectus Femoris and Iliopsoas muscles which flex the hip. Be careful if lifting the leg up leaving only the knee on the floor. If it is painful at the knee do not do it. Ensure there is plenty of padding to avoid injuring the knee.

Strengthening exercises are a very effective part of healing patella tendinopathy or jumpers knee. But knowing which exercises to do and when to do them is essential.

Strengthening exercises should begin as soon as pain allows and be gradually progressed over a period of 6 months or more. Exercises can be separated into three phases. As a guide phase 1 lasts for the first 3 months of rehabilitation and here the aim is to increase the strength and strength endurance. Phase 2, from 3 months to 6 months can begin to increase the power and speed endurance and from 6 months onwards more sports specific rehabilitation is appropriate.

It is likely that even the more serious patella tendon injuries can begin with isometric or static contractions of the quadriceps muscles. Strengthening for the calf raises is also important and can be done without much strain on the patella tendon at all. The athlete should progress to single leg eccentric squat exercises as soon as possible. Applying ice or cold therapy after performing the exercises can help avoid any pain and inflammation.

Isometric quad contractions – this exercise is likely to be possible very early in the rehabilitation program. The athlete contracts the quadriceps muscles, holds for a few seconds and relaxes. This can be done in the standing position, seated or lying face up or face down, whatever is most comfortable although standing is probably more relevant.

Initially begin with 3 sets of 8 repetitions holding for 5 seconds and build up to 4 sets of 12 repetitions holding for 10 seconds. If it is painful during, after or the next day then reduce the load. Athletes with good quadriceps bulk should aim to progress onto single leg eccentric squats as soon as possible.

Play isometric quadriceps exercise video.

Single leg extension – the leg extension machine can be used to strengthen the quadriceps muscles if doing full weight bearing exercises is still painful. It is a step on from isometric exercises but not likely to trigger the same kind of pain that single leg drop squats may.

Begin with 3 sets of 10 repetitions with light resistance concentrating on the last few degrees of motion as the leg straightens as this is the range of motion which works the vastus medialis on the inside of the knee more. Do no more on the good leg than you are able to do on the injured leg. Gradually increase the resistance when 3 sets of 10 or 12 reps become comfortable. Progress to single leg eccentric squats as soon as pain allows.

Eccentric squats – this is probably the most important exercise to get right in the treatment of chronic patella tendinopathy. The athlete can begin with double leg squats but should pregress as soon as possible onto single leg squats.

The exercise is performed by squatting down very slowly and more quickly up. Try to use the good leg to aid the upwards movement rather than load the injured knee. The aim is to load the tendon and muscle eccentrically which happens on the downwards phase of the squat. When performing single leg eccentric squats both legs can be used during the upwards phase so the load is purely concentrated on the eccentric or downwards phase.

Eccentric squat exercises can be performed on a slant board or with a half foam roller to raise the heels. This has the effect of reducing the element that the calf muscles contribute to the exercise and increasing the load on the quadriceps muscles.

Begin with 3 x 10 repetitions each day and gradually increase to 3 x 15 repetitions before increasing the load or weight. Stick with a particular load level until they can be done very comfortably. If any pain is felt during, after or the next day then take a step back. Applying ice after can help with pain and inflammation.

Play eccentric squat video (double leg only demonstrated here)..

Lunge – the lunge exercise should begin as soon as pain allows and is a more demanding exercise which brings increasing power and speed into the exercise. It is more likely this exercise will be introduced around 3 months into the rehab program but each athlete will be different.

The athlete stands with one leg in front of the other and bends the front knee so the thigh is horizontal while the back knee goes towards the floor. This can be made easier by not going quite so low with the front leg. Begin with 1 set of 8 repetitions building to 3 sets of 15 reps. A weights bar across the shoulders can be used to increase the load.

Play lunge exercise video.

Step back exercise – this exercise is more suitable for the later stages of rehabilitation when the athlete is attempting to return to more specific sports training. The athlete steps back and then in one movement steps back onto the step. This is a more explosive, plyometric exercise related to the specific demands of sport. It works the calf muscle eccentrically as well as the knee during the stepping back phase and plyometrically as they push off.

Alternate so both legs are exercised and do not do any more on the good leg than you can achieve with the injured leg.

Play step back calf rehab exercise video.

There has been a lot of published work on the benefit of eccentric exercises and in my practice I have seen significant benefits to the athletes I treat.

The key to the rationale behind eccentric drills is that they are the best way of promoting tendon remodelling: the regrowth and reordering of collagen tissue in place of the oedematous (fluid filled) degenerative tissue typical of tendinosis.

The athlete needs to be taught eccentric exercises (See table 1). A 45-degree slope is required and (at a later stage) a weights bar. Initially the athlete stands straight on the slope, then flexes his/her knees to 90 degrees, returning to a straight position again (see illustration below left).

| Stage | Exercise | No of legs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Two legs, 90 degree squat, no slope | 2 |

| 2 | Two legs, 90 degree squat on 45 degree slope | 2 |

| 3 | Single leg for squat phase (eccentric); two legs return phase (concentric), on slope |

1.5 |

| 4 | 10kg bar; single leg for squat phase, two legs return, on slope |

1.5 |

| 5 | Single leg only throughout, on slope | 1 |

The movement down must be done slowly (to a count of three) and the return can be done quickly (to a count of one). When away from home the slope can be replaced by the edge of a curb or step so that opportunities can be taken whenever possible to do the drills.

The number of repetitions is determined by the amount of discomfort felt in the patellar tendon. I advise athletes to stop a sequence of repetitions when they perceive an ache in the patellar tendon of 3/10, using the scale described above. The rationale for this is to stimulate the patellar tendon eccentrically to a fixed (symptomatic) level each day, but without such a high score as to produce pain and further damage. I suggest to athletes that they can do these repetitions as often as possible every day and many achieve the repetitions two to four times a day.

The exercise sequence can be progressed as shown in table 1. For some athletes stage 1 is too easy and they cannot bring on any discomfort in the patellar tendon. For others, the ratelimiting factor is quadriceps fatigue and for this reason they can use two legs in returning to the standing position (see stages 2 to 4).

As the stages progress the athlete will be able to increase the number of repetitions they can perform before the symptoms come on at a discomfort level of 3/10. There will be some days when the athlete can manage more repetitions than others, but normally they will be able to move on to the next stage after two to four weeks – so improvement in this condition is usually measured in months, not weeks.

The rate of progression will vary from athlete to athlete, dependent in large part on how often they perform the exercises. If more pain occurs in the tendon, the athlete should be advised to rest for two to three days and then drop back one stage in the rehab exercise progression.

Alongside the eccentric exercises, it is important to address other possible contributory factors, such as:

Every knee has a medial and lateral meniscus which are C-shaped pieces of fibrocartilage that absorb stress and act as cushions between the bones at the knee. At birth, the meniscus is not C-shaped, but discoid (round like a discus).

With growth and walking, the discoid meniscus evolves into its normal C-shape. In some children, the lateral meniscus continues to stay discoid with growth.

| Classification | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Presentation | |

|

| Imaging | |

|

| Treatment | |

|

Traditionally, the treatment of choice for symptomatic stable or unstable discoid lateral meniscus was open total meniscectomy. The residual meniscal tissue that had been left after partial meniscectomy was considered abnormal and was, therefore, supposed to be resected as well [9, 15, 24, 25]. The menisci serve as load distributors and shock absorbers and play a role in joint stability as well as in synovial fluid distribution and cartilage nutrition. Better understanding and documentation of the importance of the menisci to normal articular function has led to preservation of stable meniscal tissue as part of treatment planning.

Partial meniscectomy of normal shaped menisci, was shown to increase the contact stresses in proportion to the amount of removed meniscus [49]. Following total meniscectomy, the contact area was decreased by 75% while contact stresses increased by 235% [49]. The lack of normal meniscal fibrocartilage arrangement in discoid menisci types 1 and 2 may play a roll in load changes after partial meniscectomy of lateral discoid meniscus, but no data supporting it has yet been published. A meniscus-deficient knee carries a high risk of early cartilage degeneration and early degenerative changes. Total meniscectomy of a non-discoid meniscus often leads to osteoarthritis [50–54]. Bearing in mind the detrimental effect of meniscectomy on the knee’s function, the goal in treatment planning should be preservation of meniscal tissue.

Incidentally found discoid lateral meniscus with no symptoms or physical signs should not be treated surgically. A periodic follow-up for exclusion of symptoms and a physical examination enables early detection of any deterioration and appropriate treatment planning.

Snapping knee with no other symptoms and no radiographic signs of accompanying articular lesions can be followed-up and then treated should it become symptomatic. A patient may become symptomatic due to instability of the meniscus, a new tear of the ill-defined meniscus, or as the result of accompanying findings, such as osteochondral lesions to the lateral joint compartment.

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (saucerization) is the treatment of choice for symptomatic stable, complete, or incomplete discoid lateral meniscus [8, 30, 55]. The width of the remaining peripheral rim is an important feature to consider when meniscectomy is performed. Most authors agree that the width of the remaining peripheral rim should be between 5 mm and 8 mm to prevent impingement and instability of the remaining part of a discoid lateral meniscus that may lead to future secondary meniscal tear [55, 56]. If a meniscal tear is present, partial central meniscectomy in conjunction with suture repair of the peripheral tear can be effective treatment [57] (Fig. 3a–c).

The reparability of the lateral discoid meniscus cannot be reliably predicted from imaging studies, even MRI [58], and can best be decided on intraoperatively. Klingele et al. [59] reported that 28.1% of arthroscopically evaluated discoid lateral menisci had peripheral rim instability; therefore, the planning and preparation of surgery should include anticipation of a possible need for meniscal stabilization by suturing.

Motoric and radio frequency tools are used for meniscal reshaping. When meniscal instability is found clinically or arthroscopically, stabilization of the meniscus should be considered providing that the meniscal tissue quality allows it. We usually use an inside-out technique for meniscal suturing and use the all-inside meniscal devices for augmentation.

Type-III unstable lateral discoid menisci can be reattached to the posterior capsule and complete meniscectomy should be condemned.

Finally, despite technical improvements in arthroscopic surgery, arthroscopic procedures for treatment of discoid meniscus are considered technically difficult due to the abnormal size, height, and quality of the discoid meniscus [28, 30].

Meniscectomy of the lateral meniscus harbors a detrimental effect on the lateral knee. A retrospective review of patients who underwent arthroscopic partial lateral meniscectomy for lateral meniscus tears demonstrated that early results for partial lateral meniscectomy could be quite good, but that significant deterioration of functional results and decreased activity level can be anticipated [60]. The results of total or near-total meniscectomy of non-discoid meniscus in pediatric patients are poor, with the risk of early arthrosis [52, 53].

There has been a trend toward choosing meniscal preservation procedures for treating discoid lateral meniscus. Aichroth et al. [28] reviewed 52 children with 62 discoid lateral menisci and an average follow-up of 5.5 years. The children’s average age at operation was 10.5 years and the mean delay in diagnosis was 24 months. Of knees with symptomatic torn discoid menisci, 48 underwent open total lateral meniscectomy, 6 had arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, and 8 with intact discoid menisci were left alone. The reported outcomes were 37% of the knees with excellent results, 47% with good results, 16% with fair results, and no poor results. Early degenerative changes were seen in the lateral compartment in three knees of older patients (over 16 years of age) with a follow-up period of 11, 13, and 18 years after total meniscectomy. The authors concluded that arthroscopic partial meniscectomy should be recommended only when the posterior attachment of the discoid meniscus is stable and that total meniscectomy is indicated for the Wrisberg-ligament type of discoid meniscus with posterior instability.

Washington et al. [61] reported good or excellent results in 13 of 18 knees of patients with a mean age of 17 years (8–28 years). Radiographs of 9 knees (8 patients with a mean age of 15 years; 7–26 years) showed evidence of slight narrowing of the joint space in only 3 of them.

Raber et al. [62] reviewed the results of total meniscectomies performed in 17 knees (14 children) for discoid lateral meniscus at a mean follow-up of 19.8 years (range 12.5–26.0 years). They found that 10 of these knees had clinical symptoms of osteoarthrosis. Plain radiographs were available for 15 knees and 10 showed osteoarthritic changes.

Aglietti et al. [63] reported 10-year follow-up results of arthroscopic meniscectomies for symptomatic discoid lateral menisci in 17 adolescents. They found no correlation between the type of meniscectomy (partial or total) and the clinical and radiographic results. Development of radiographic changes, such as minor osteophytes in the lateral compartment of 8 knees and less than 50% narrowing of the lateral joint space, was found in 11 knees. The reported clinical results were excellent or good in 16 of their 17 patients.

It should be emphasized that excellent or good clinical reports after a 10-year follow-up in this age group calls for a critical appraisal. The follow-up period puts those patients in their mid-to late twenties. In the face of the reported high incidence of ominous premature radiographic arthritic changes in this and the other series, a longer follow-up period is needed.

Currently, the indications and results of treatment options, such as meniscal transplantation for knees with a history of discoid lateral meniscectomies and meniscectomy, have not yet been conclusively defined. There is some experience in performing allograft meniscal transplantation for those cases but no reports have appeared in the literature thus far. Heightened awareness of the clinician to the possibility of discoid meniscus, its variable presentations and complications, and management considerations may improve therapeutic outcome.

VIDEOS

Before AIDS epidemic, PML was considered a rare complication of the middle-aged and elderly patients with lymphoproliferative diseases and incidence of PML in pre-AIDS era was considerably low (0.07%) [12]. It is now a commonly encountered disease of the CNS in patients of a variety of different age groups with AIDS and ~5% of HIV patients develop PML. It is now defined as an AIDS-associated illness. In addition, recent studies indicate that the highly active retroviral therapies (HAART) against HIV infections considerably reduced the virulent behavior of HIV virus, however, the same does not hold for JCV infections. In other words, the incidence of PML did not significantly change between the pre-HAART and post-HAART era [13]. More interestingly, PML has also recently been described in patients with autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease, who were treated with specific monoclonal antibodies. These antibodies (natalizumab and efalizuma) target several surface molecules (α-integrin) on B and T cells and prevent their entry into brain, skin and gut. Rituximab, another monoclonal antibody, targets the CD20 surface molecule on B cells and causes their depletion through complement-mediated cytolysis.

PML stands for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy- ok lets just stop right there and breakdown that mouthful…

Progressive- steadily getting worse

Multifocal- in many areas

Leuko- white (in this case referring to white matter in the brain)

Encephalopathy- disorder or disease of the brain

So before even reading anything else you already know that this is a disease that afflicts multiple areas of white matter in the brain, and that it gets worse over time. But what causes it?

PML is in a category called “opportunistic infections”. These are infections that generally pose no threat to a person with a normal immune system, but love to rear their ugly heads in people with weakened immune systems. They are most frequently seen in chemotherapy patients or people with HIV because they are severely immunocompromised. Although it is much rarer, they can also occur in people with MS who are on drugs that weaken their immune systems. You may already know that Tysabri poses the greatest risk for developing PML. However, PML developed in one person taking Gilenya, and one person taking Tecfidera recently died of complications from a PML infection.

The JC virus (John Cunningham virus) is the infection that leads to PML. This virus behaves much like other common viral infections such as herpes and the chicken pox. When you get the chicken pox the virus never leaves your body, and later in life it may flare up again and cause a condition called shingles. Similarly, people who have been infected with herpes always have the virus lurking in their nervous systems. During times of stress it will become active and an outbreak of sores will occur, but unless an active outbreak is occurring there are no outward signs of the virus. The JC virus is fairly common, and is passed easily from person to person. However, since it’s an opportunistic infection healthy people never have any complications from it. When you introduce medications that weaken the immune system, like Tysabri does, your body no longer fights off viruses the way it used to. This gives the dormant JC virus the chance to become active. Once it is active there is a chance that it can cross through the blood-brain-barrier and cause PML. This causes severe damage to the white matter of the brain, and can even lead to death.

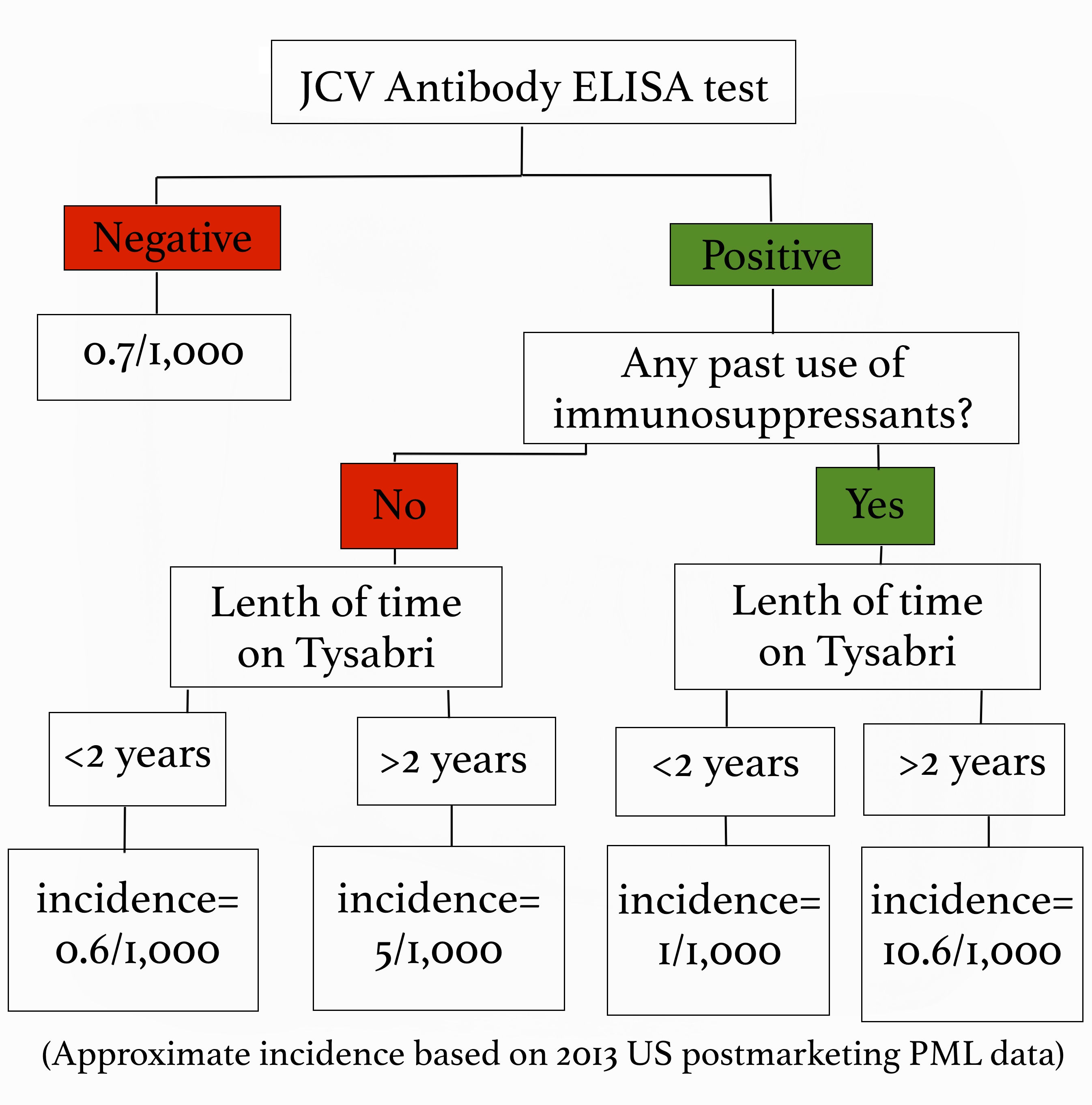

All of that information is fairly terrifying right? Well, here’s some good news! We can easily test to see if you have been exposed to the JC virus, which tells us if you are at risk for developing PML. A blood test called the JCV Antibody ELISA test is routinely done on anyone thinking about going on Tysabri. If you test negative, meaning you don’t carry the JC virus, we continue to test for it every 6 months while you are taking Tysabri because you can be exposed to the virus at any time. If you do test positive we also get an index value, which gives us even more information about how likely you are to get PML. A low index value indicates a very low risk, and a higher number indicates a greater risk. All that being said, PML is by no means a common side effect. However, when it does happen it is very serious, so we as providers aren’t willing to take any chances! During the first year of taking Tysabri your risk is very low, but it increases after two years. Additionally, being treated with immunosuppressants in the past puts you at a higher risk for developing PML. We look at all of these risk factors, and use that information to decide whether Tysabri is safe for you or not. The benefit of Tysabri is that it lowers relapse rates by 81%, and disability progression by 64% so we have to weigh its effectiveness against the relative risk of contracting PML, which I’ve summarized for you below:

Because PML attack the myelin, just like MS does, the symptoms should sound familiar. They include confusion, difficulty talking, weakness, memory loss, and loss of balance and coordination. If PML is suspected a MRI of the brain will be done, and a lumbar puncture can confirm the diagnosis. PML is treated in the hospital, and the goal of therapy is to remove all traces of the virus from your body.1-6

Picking medications is a very personal decision, and should be discusses in detail with your neurologist. It is imperative to weigh the risks versus benefits very carefully, and to understand the medications and their side effects. Being well informed is the first step to being your own best advocate!

Diagnosis

Although PML lesions, caused by both lytic infection of oligodendrocytes and neuronal loss, can be detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system [33], some other CNS related viral infections may make this diagnosis difficult. Therefore, detection of JCV in the brain samples of PML patients in large numbers would be strong evidence for the full diagnosis of the disease. There are a number of techniques for the identification of the virus as the causative agent of PML, including immunocytochemistry and nucleic acid methods. Antibodies against JCV were employed earlier; however, the specificity of this method was always in question due to cross-reactivity with other viral proteins. Nucleic acid methods, such as in situ hybridization of JCV DNA were successfully performed on tissue samples obtained from various PML patients [34]. However, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been proven to be the most reliable method for detecting JCV DNA in PML cases. PCR can easily be used to test cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for infectious JCV. In a recent study, it has been shown that as low as 10 copies of viral DNA in CSF can be detected using quantitative PCR technology [35].To support this finding, in another recent study, 168 suspected PML cases over 10 years have been reviewed retrospectively and it turned out that majority of the samples that are diagnosed as JCV positive using PCR come from HIV positive patients [36], which highlights the importance of HIV infection in JCV reactivation.

Enliva is a new active supplement containing 3 specifically selected and patented strains of beneficial bacteria – Lactobacillus Plantarum (CECT 7527, 7528,7529). Enliva is intended for use by healthy patients not yet requiring prescription medication, who are seeking to maintain healthy cholesterol through diet and exercise. Enliva is specifically formulated to support these activities to help maintain normal cholesterol levels. Enliva is a once-a-day complementary medicine that may help to maintain normal cholesterol levels in healthy individuals in two ways; Increasing the use of cholesterol by the liver: the enzymes from Lactobacilli in Enliva have been shown to promote the breakdown of bile salts. Once broken down, bile salts are not available for use by the body and are removed. To replace the lost bile salts, the liver takes cholesterol from the blood to make new bile salts. Reducing the amount of cholesterol absorbed from the diet: The bacteria in Enliva has also been shown to absorb cholesterol which is then removed in normal digestive waste.

L-Argenine and N-Asetyl cystine

HDL,LDL, cholesterol

mmol/L to mg/dL / by 0.0259 to get mg/dL

mg/dL to mmol/L * by 0.0259 to get mmol/L

HDL,LDL, cholesterol

mmol/L to mg/dL / by 0.0259 to get mg/dL

mg/dL to mmol/L * by 0.0259 to get mmol/L

Triglycerides

mmol/L to mg/dL / by 0.01129 to get mg/dL

mg/dL to mmol/L * by 0.01129 to get mmol/L

EXAMPLE 1 DAD

Cholesterol 4.2 mmol/L 162.16 mg/dL Triglyceride 0.8 mmol/L 70.85 mg/dL HDL 1.11 mmol/L 42.85 mg/dL needs to be >60mg/dL LDL 2.7 mmol/L 104.24 mg/dL needs to be <70mg/dL Chol/HDL Ratio 3.8 mmol/L

EXAMPLE 2 MUM

Cholesterol 7.6 mmol/L 293.43 mg/dL Triglyceride 1.7 mmol/L 150.57 mg/dL HDL 1.71 mmol/L 66.02 mg/dL needs to be >60mg/dL LDL 5.1 mmol/L 196.91 mg/ dL needs to be <70mg/dL Chol/HDL Ratio 4.4 mmol/L

LDL’s

Bad Fats and promote atherosclerosis (narrowing of the arteries)

An LDL level of less than 100 mg/dL is optimal for CAD prevention,

A level of 70 mg/dL or less is now recommended for persons with existing heart disease

HDL’s

Good Fats and promote opening up of the arteries

> 50 mg/dL (≈ 1.3 mmol/L) man or >60 mg/dL (≈ 1.6 mmol/L) in a woman a reduced risk of atherosclerosis.

>75 mg/dL (≈ 2 mmol/L) man or woman is associated with a very low risk of atherosclerosis.

Less than 40 mg/dL (≈ 0.8 mmol/L) in a man <50 mg/dL (≈ 1 mmol/L) in a woman increases the risk.

TRIGLYCERIDES

Reduction of triglycerides to 60 mg/dl.

Dr Thomas Challenger ![]() Challenger Mission

Challenger Mission